Contents of this chapter

At several points in this memoir, I have emphasized the value of conferences to O’Reilly, to the communities we served, and to my own growth. The best way I can demonstrate this value is a story from a conference I nearly didn’t get to attend. And I certainly didn’t know what the conference was until I got there.

My revelation had to do with the role of the author in modern media. Writing used to be a ponderous endeavor: the shuffling of foolscap sheets decorated by the carefully honed quills dipped into an inkwell that needed frequent refilling. When did writing get stripped down to telegraphic phrases? And did that metamorphosis elevate or degrade it? After seeing new media abused so thoroughly that they eviscerate democracy and the notion of truth itself, one would certainly say the latter. But I realize that different levels of writing—from the cursory to the exhaustive—benefit each other. I had to learn this from a children’s book writer on a continent five thousand kilometers away.

I got to Barcelona through a friend I had made in my volunteer work for Computer Professionals for Social Responsibility, David Casacuberta. A Spaniard who moved to Catalonia but still preferred speaking Spanish to waiters decades later when I had dinner with him, Casacuberta was one of those academics who straddled computers and the social sciences. His research changed from year to year, but generally concerned effective ways of applying computer science to social problems, and the effects computer science have on society. It’s a perfect occupation to pursue in Barcelona, which for centuries has been on the technological leading edge and is determined to stay there.

Casacuberta, who was one of the few members of CPSR in Europe, first contacted me in 1998 to thank me for an article I published in The American Reporter about fascist propaganda. In this article, “Nazis, Neos, and Other Nasties On the Net”, I boldly stated that we should not tolerate these perennial threats in our public places. Although I called for some forbearance online, because their postings did not create an immediate physical threat, I recognized that they could still be dangerous.

My balanced approach, although it certainly did not solve the problem (as we found later when the “alt-right” took over public discourse), was a contrast to the standard Internet activist view in the United States. Most American free speech advocates on the Internet simply said that anything goes, and that in a marketplace of free expression the truth will win out.

Europeans, having lived through Nazism, kept a more guarded view, and Casacuberta congratulated me on recognizing that there are many legitimate views on the subject of fascist speech. We kept up our correspondence over the years, and in 2006 he approached me with an intriguing request.

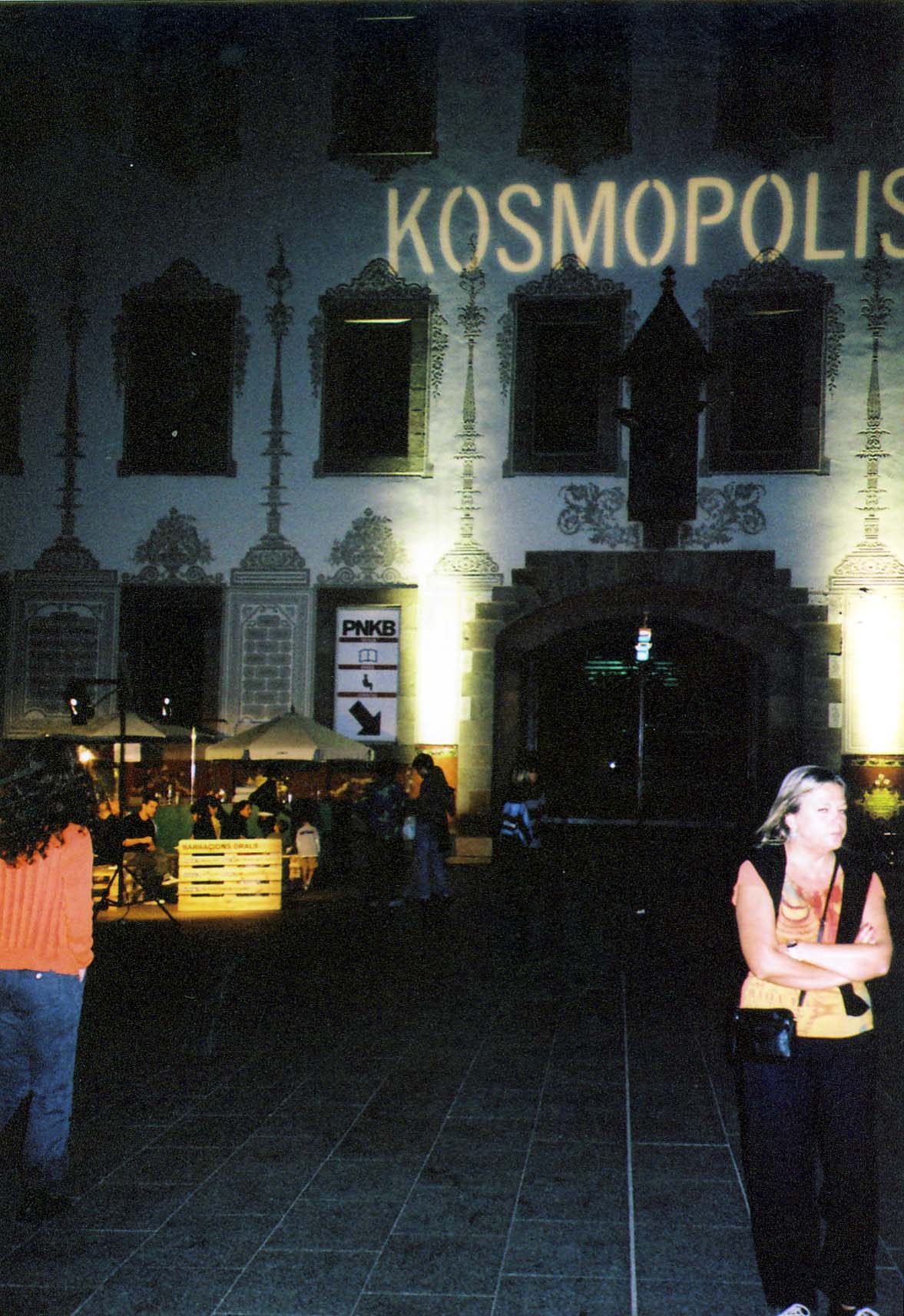

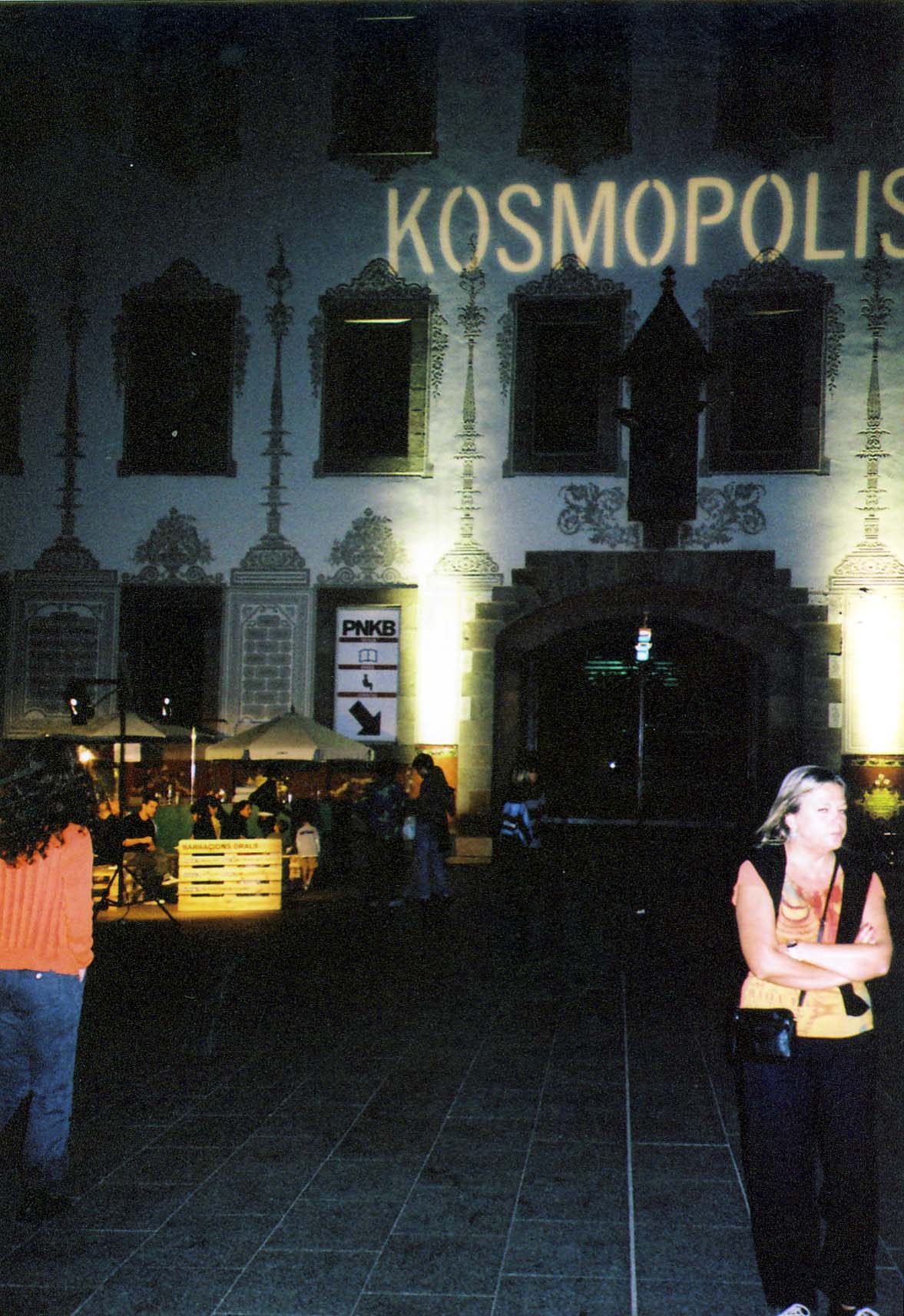

Barcelona hosts an offbeat conference called Kosmopolis—one I had never heard of, and whose existence I could scarcely imagine. Held at the historic Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona (CCCB), Kosmopolis treats of all things creative in all media. It has a special interest in what new technology offers the arts.

Casacuberta played some role in planning the 2006 conference, and was tasked with asking Tim O’Reilly to speak. Because he had no direct link to Tim but knew I worked at his company, Casacuberta asked me to convey the invitation to Tim.

I lost no time blowing my own trumpet. I wrote back saying, “If Tim comes, he’ll deliver the same business-oriented speech he gives at industry forums.” I actually had no idea whether that was true, but sensed it to be. I continued, “If you bring me instead, I can give a talk tailored to the topics the audience is interested in.” Casacuberta said he appreciated my insight, but that the other conference organizers wanted a “big name” that would draw more attendees, and for that reason had specifically demanded Tim.

My aggressiveness was matched by my luck that day. Tim thanked the organizers but said that he was already booked at the time of the conference. I was the second best choice, but Casacuberta said he would sign me up to keynote at Kosmopolis and even admitted that I was the person he had wanted in the first place.

I haven’t forgotten that I started this story as a lead-up to my revelation about writing on the Internet. But I must describe Kosmopolis itself first, because it was such a magical backdrop to a magical evening.

Kosmopolis runs on Iberian time, meaning that sessions begin at 6:00 PM each evening and go to about 11:00. That meant I could be a tourist all day and still attend the entire conference. Conference sessions included conventional talks like mine along with films and various kinds of performance art, such as a young black man who put together a rambling discussion on Colin Powell (former Secretary of State), tying together his lies in the service of the Iraq invasion with other aspects of his life, including a digression into possible incontinence that the speaker demonstrated on stage.

For my own keynote, I had prepared a summary of how I used the Internet for personal and work-related publicity. I could cite substantial experience here. I had published an article creatively exploiting the Web’s distributed structure in the first issue of O’Reilly’s early online journal, Global Network Navigator, which pioneered both advertising and edited content in 1993. In 1997, I had been highlighted in Fast Company magazine because I was staking out new ground by using the Web to promote my work. I was constantly looking for new ways to market O’Reilly’s work on the Web in an age when social media hadn’t caught on yet. (I didn’t realize that being featured in Fast Company was anything to boast about until O’Reilly’s publicist Sara Winge chided me for not letting her know so that she could capitalize on the achievement.)

Furthermore, I had just finished an article called “Characteristics of new media in the Internet age” that laid out a broad history of human creativity and divided it into three phrases. The first phase was the huge pre-printing era going back to the beginnings of consciousness, followed by an age characterized by strong copyright and the inviolability of the statement by a single genius, and now a totally new age that would be characterized by ever-changing works of art on which many people would collaborate. Sometimes, grand historical surveys like this appeal to me, even though I know they are crude and hide important disqualifying details.

All told, though, I don’t think my talk was offering much new—not really worth traveling three thousand miles.

I was paired with a popular Peruvian author, Santiago Roncagliolo (a convenient pick because he was living in Barcelona), who had similar stories to tell about using online media.

The one truly clever moment in my talk was improvised. Just before going on stage, I met Roncagliolo, who let out that he doesn’t like Bob Dylan, and that his readers sometimes harangue him for that. So in my talk, I added a short section about people being confused by the opportunities offered by the Internet, and ended with the comment, “It’s like Bob Dylan said—you know something is happening but you don’t know what it is.”

How ironic that I should tease my fellow presenter that way! In truth I was describing myself. I didn’t know what was happening, but over the next 24 hours I would find out.

A woman in her 30s stood up during the question-and-answer phase of the keynote and spoke passionately in Spanish (possibly Catalan—I don’t remember). I did not understand, and some members of the audience tried to translate, but what they said was too fragmented to make sense.

But I had another public appearance at Kosmopolis: a workshop I held the next day. The same woman came again, tried to convey her comments again, and failed again to get through to me.

I saw her in the courtyard afterward, and in halting Spanish told her I regretted not being able to understand what she said. She responded, “Parlez-vous français?” I did indeed! We had finally found a common tongue. And everything flowed from that.

The woman was named Georgina Rôo and was born in Argentina, but had spent time in France before moving to Barcelona. She had written at least one children’s book and was now offering photos and stories on an online media site. Because we didn’t have laptops, we repaired to the speaker’s lounge, where Kosmopolis had provided speakers with access to some large desktop systems. As other speakers crouched over computers or rushed meals, Rôo brought up her web site and explained her discoveries.

One of her favorite online activities was to post a photograph on which readers would comment. Often these comments would prompt her to take a fresh look at the picture and at her own story embodied in it, prompting ideas for new writing. In other words, for her the Web was much more than a site for publication and self-promotion. It created a dialog between her and her readers, and her readers helped to shape her content.

As I mentioned, social media was still a relatively new phenomenon in 2006. Friendster and MySpace had been offering forums for personal promotion for a while, but didn’t seem to be changing the relationship of the individual to the collective. Facebook had been founded but was immature. What Rôo told me revolutionized my thinking about the creative potential of the Internet.

By now we felt like old friends. We had dinner together, and after the conference we connected on Facebook, where I could read her occasional Spanish-language postings. By the time I got back to Barcelona with family over a decade later, unfortunately, Rôo had returned to Argentina. But Casacuberta was still there and met me along with my wife for dinner.

Such is the magic of a conference. I flew out to Kosmopolis cock-sure of what I knew about authors on the Internet, and I returned with a new understanding of what I did not know.

During the years when I attended two O’Reilly conferences per year—the Open Source Convention and the MySQL conference—as well as other interesting events, I cranked my gears up to the highest energy level and adopted a punishing schedule. Arriving in Portland, Oregon or Santa Clara, California on East Coast time, I would rise by five in the morning, sample the news (which during the early years could be found only in paper form), and have breakfast, which I often set up as a business meeting with a potential author or other valued contact.

This led—perhaps with a gap of a few minutes in which I could continue to catch up with news or with my email—to a full day of keynotes and sessions, punctuated with video interviews of leaders in the technical, business, or social aspects of the field, and with lunches scheduled months in advance among the key people with whom I wanted to deepen relationships and pursue future opportunities.

Nightfall brought only a different nuance to the treadmill of learning, networking, and celebration. I typically found a meal—sparkled up with alcohol—sponsored by a vendor or other organization that I wanted to draw closer to, and then went to several of the informal evening meetings that were held by a luscious variety of communities.

O’Reilly called these after-hours meetings “Birds of a Feather” sessions. We took this term adopted from Usenix, the classic gathering of researchers, system administrators, and community activists who circled around Unix. During these evening gatherings, the conference venue felt completely different. Daylight sessions teamed with people who rushed from one event or rendezvous to another, and who included groupies and hangers-on from marketing departments and the media. For the Birds of a Feather sessions, a kind of holy repose settled over the vast, open, featureless space. Coming upon a community discussion felt as if entering a sanctuary of the elect.

In Birds of a Feather sessions, speakers who had conducted formal sessions during the day could exchange views with their most dedicated followers in a less constrained moment. New projects that were too small to merit a formal conference session could present their vision and promise in order to alert technologists aiming for the next big thing in their field. Developers who exchanged ideas throughout the year over email and IRC (an early form of online chat) could sit side by side and lay plans for the upcoming year.

When the conference venue finally emptied out, at nine or ten at night, I would lug the laptop that had been fixed like a scabbard to my side all day back to my hotel room, and would whip out a blog posting in half an hour covering events of the day. After a final click putting the article up on the O’Reilly web site, I went to bed with a sense of fulfillment to prepare for a repeat of the routine the next day.

The interviews at our conferences provided an extra jolt of excitement as well as pressure. O’Reilly wanted to air interviews of five to ten minutes with industry leaders, as enticements to get more followers and encourage outsiders to come to our conferences. Sometimes I knew in advance some key attendees and could solicit a short interview on-site. Often, though, I heard interesting speakers or were introduced to people in the hallways or after-hours events and spontaneously asked them for interviews. I was certainly happy to interview major technology leaders, but also sought out voices that weren’t usually heard, fostering diversity in race, gender, and geography as well as fringe projects offering promise.

In any case, scheduling was difficult. The video staff came for just one or two days with scattered fifteen-minute slots, and I had to coordinate the staff’s openings with my own free time and that of the speakers.

I worked out many of the questions in advance, and my interviews always struck interesting points. Just one time I was disappointed, because of a poor decision made by the person I asked to interview. I had known someone in the open source health care movement (a rather tiny community) who got involved in a major UN-backed project. After we met in an open area at the Open Source Convention, he introduced his project to me with passion and insight, and I set up an interview.

Shortly before the interview was to take place, he called to say that he’d rather have one of the project’s marketing people talk instead, and I gullibly agreed. The marketing person turned out to be all veneer—and a cheap veneer at that. Not only did he lack the historical depth and technical knowledge shown by the colleague I had invited originally, but he didn’t even seem to know that such things were important and of interest to an audience. This fiasco taught me to trust my own instincts when choosing speakers to interview.

For many years, the Open Source Convention gave shelter to another unique event, the Community Leadership Summit. This, like the Velocity conference, grew from a book that I proposed and edited. In this case, open source advocate Jono Bacon (more of a rock musician than a coder) had noticed that free software developers were grasping the importance of the communities in which they worked or volunteered, and also noted the challenges of maintaining a healthy and productive atmosphere. The term “community leader” was coming into use around this time, the mid-2000s, although I don’t think it was yet honored with a job description and treated as a paid position. I believe that, at first, the role was taken on by dedicated community members, who forged its practices out of experimentation and tough experience. Bacon pitched the book Art of Community to us. He penned a wonderful exploration into many aspects of the field that sold extraordinarily well.

Bacon then proposed a conference that would piggy-back on the Open Source Convention. O’Reilly paid for a few rooms during the weekend preceding the convention, and several other companies stepped up to provide funding. But the amenities were frugal. As an example of this bare-bones organization, each person as they arrived wrote their own badge. In later years, I picked up on a trend permeating hip organizations and encouraged everyone to write their preferred pronouns on their badges. In this way I honored my own transgender child, while bringing us into the cultural shift adopted by other gatherings in the 2010 decade.

Volunteers checking in attendees to the Community Leadership Summit; Jono Bacon on the left

Everything else about the summit was pretty spartan, too. Lacking enough room for breakout sessions, we crowded about the round tables dotting the hallway and suffered from noise and distractions. Still, holding the conference in a set of rooms off the single hallway, which stretched in a wide leisurely circle with no corners to break one’s view, brought us all into close association.

The summit served coffee and tea in the morning, assenting to the pumped-up catering charges required by the convention center, but asked people to scatter to nearby restaurants in Portland for lunch. The problem: There were no restaurants conveniently nearby (a puzzling dearth for a convention center that could gracefully host at least three large conferences simultaneously). The couple of sandwich places a few blocks away were soon overflowing with summit attendees, while some turned up their noses at these options and jumped on the light rail to savor the greater gastronomic opportunities downtown. Both sets of attendees were usually late getting back to the afternoon sessions.

But the spirit and quality of the Community Leadership Summits, which O’Reilly agreed to sponsor for many subsequent years, were electric. Who can network and exchange information more competently and entertainingly than community leaders?

The format was that of an “unconference”, a forum driven from the bottom up. Neither sessions nor speakers were planned in advance. Instead, we trusted the expertise of the attendees, and allowed anyone to propose a session at the start of the day. People decided on the spur of the moment which sessions to attend.

The idea for an unconference was popularized by O’Reilly invitation-only events called FOOs (standing for Friends of O’Reilly), although I believe the idea of an unconference, and perhaps the term as well, predated the first FOO. At the Community Leadership Summit, Bacon bent the unconference ideal a bit by offering keynotes as other conferences did. Toward the end he adopted a more standard conference format.

Topics at each summit were as varied as the attendees. The summits were so intriguing and unprecedented that they attracted people not associated with free software. I was amazed to find people who flew long distances for the Community Leadership Summit without even attending the Open Source Convention that followed. The summit had an audience and a community of its own.

As an example of the bonds one could form, one activist in free software named Jeffrey Osier-Mixon met with me just once a year when we both attended the summit. I believe our very first meeting took place during the excitement of the initial summit, perhaps at the very beginning of the day. Many lively conversations followed. We had no particular project to work on together, and rarely exchanged messages during the rest of the year, but re-established the relationship at each annual summit. Our conversations were of the type where a couple words and cocked head could convey shared values and a common understanding. Friendly, cheerful, and always ready with a smile, Osier-Mixon gave off the sincerity of someone who cared deeply for causes. Many years have passed since we talked, although we’re connected on LinkedIn.

I offered two sessions regularly at each CLS. The main one brought up my obsession with how to produce documentation by volunteers within free software communities. This session was related to the research topic I informally pursued for many years and even thought of making into a new career. My forum was always well attended and drew people who knew more than I did about producing such documentation.

Regarding documentation, incidentally, I was one of the people who assiduously posted minutes from the CLS sessions I had attended, so that people anywhere in the world could get some benefit from our discussions.

The other topic I spoke on a few times, including a keynote with slides at one CLS, concerned lessons that organizers at the conference could learn from classic community organizing—the 1940s movement started by Saul Alinsky and still embodied in the Industrial Areas Foundation. I explained my own growth as an organizer and some of our successes.

The summits return to my mind wrapped in an aura of emanating potential. Although plunked down in an uninspiring physical setting, with cavernous hallways and windows looking out at highways, each assembly of volunteers representing far-flung communities and places built a place of acceptance, mutual support, eager inquiry, and even mutual love. I think that a bit of the spirit of Portland, a depository for searchers and misfits, contributed.

Attendance at the summits, however, extended my conference participation to the point where it stretched my stamina past the breaking point. Two days of Community Leadership Summit plus five days of Open Source Convention were too much for my constitution. Around the fourth day of one Open Source Convention, I admitted in my blog post that I took off an hour “to get a more horizontal view on things.”

Another time, poor planning brought me low. I held back on food consumption through the whole day, anticipating the hors d’oeuvre to be served at an evening event. But I was keeping somewhat kosher (an observance which I’ve adopted and abandoned at different points in my adult life), and saw at the event that everything had bacon, shellfish, or some other traif component. So I refrained from eating, but partook freely of the alcohol. I went briefly to another conference party but wisely left the liquor alone, realizing that I’d overdone it at the first party.

Dawn brought with it a terrible headache, and I stayed in bed till lunchtime. I then dragged myself down to the show floor and plopped myself into a seat in the O’Reilly booth. Jono Bacon came by. I pointed to a professional actor who, cavorting as part of a vendor promotion, was walking around the show floor fully covered in a bunny suit. I told Bacon, “I know I’m suffering from a hangover, but this is ridiculous.”

Alcohol causes a lot of evil at professional conferences (contributing to dangerous behaviors such as sexual assaults) but remains a key element of connection and community celebration. I heard one person riff on the popular term “peer-to-peer” to claim that the most productive developments at conferences occur “beer-to-beer”. At the Open Source Convention and MySQL conference, insiders could sample the unique licorice-flavored black vodka brewed by Monty Widenius, the creator of MySQL, at either a Birds of a Feather session or a private party.

For many years, one of my most common type of dream locates me at some conference—never a real-life one, but some fictional conference meeting about some cloudy notion. This conference is always held in an intriguing and mentally stimulating space very different from the desolate venues for most real-life conferences. I think that these recurring dreams are concocted from the actual experiences of personal connection, enlightenment, and joy I have had throughout my career at conferences.

FOO conferences were special because of the extremely limited invitation list. People occasionally complained that they were invited to one FOO but passed over the following year, but that’s because the whole point was to rotate experts. There was a sort of natural ceiling to the number of people who can construct a temporary, weekend-long community—about a hundred and twenty, reminiscent of Dunbar’s number.

FOO pushed the boundaries of behavior physically and mentally. I minimized sleep at these events, because one could pop in on interesting conversations until two or three each morning, and productive interactions started again around six. Although some attendees literally camped out at the O’Reilly campus in Sebastopol, I just found a quiet spot in one of the buildings, bedding down with my backpack as pillow and my jacket as blanket.

A few attendees would retreat to the comfort of local hotels at night, but most of us didn’t want to miss a minute. After all, we were constantly rubbing shoulders with world leaders in computing, science, education, and other fields. A few health FOOs were held during O’Reilly’s period of interest in health IT, either at the Sebastopol campus or at the conference space offered on the tenth floor of Microsoft Research in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Both spaces offered nooks where people could meet quietly for brainstorming.

But that kind of untrammeled headiness can turn bad. For me, FOO conferences were kaleidoscopes of wonder. But I heard later that various forms of licentiousness took place, including assaults. I never saw those things myself.

Raised to be frugal, I always took note of the expense of conference travel. I can’t remember ever crossing the country on a non-stop flight for a conference, because I always looked for a cheaper option. I wouldn’t reserve a room in the block reserved by O’Reilly, unless they encouraged me to fill a block they had reserved in advance. I enjoyed the task of finding a budget hotel within walking distance of the conference center. And one manager, Frank Willison, expressed his appreciation when I told him that I was staying at a cheap hotel four blocks from the conference site and carrying a box of books there by hand. (That was not for an O’Reilly convention, but for an Ottawa Linux Symposium, a highly sought-out place to watch the sprouting of new kernel development.)

My son, as a teenager, was trying once to get his head around the concept of an expense report and the trust that managers must grant the employees who claim reimbursements. Have I ever submitted false expenses, he asked?

This is one of those moments when a parent can help shape his children’s approach to life. Although expenses require receipts, that is scant protection against skimming off the top, because profligacy can be disguised or receipts padded.

With my son, my goal was not just to demonstrate proper morals but to ground them in good sense. So I said that I try to minimize expenses, and never pad them. This is not just because doing so would be unethical, I explained, but because every dollar I take for myself is a dollar that my company can’t invest in its growth. And I figure that a successful and expanding company will benefit me more in the long run than charging an unnecessary restaurant meal.

My attitude loosened a bit after one Open Source Convention in Portland, Oregon. I saw a colleague from Washington, DC at the site the day before, and asked him whether he was staying for the conference. No, he told me, O’Reilly had flown him out just for that day to attend a meeting. I decided that I did not have to show any more concern for travel expenses than my managers did. Nonetheless, I did not start frequenting three-star Michelin restaurants, or even fly non-stop.

There was no need to credit altruism in the way I put O’Reilly’s needs first when talking to my son. I always identified the company’s financial success with my own. You have seen several examples of this in the memoir. Here’s another.

During the mid-1990s, when editors were high priests who directed every turn taken by the company and lapped up a sizable portion of the resulting bounty, we hit a rough spot financially, perhaps an augur of the crisis to come in 2001. I wrote to Tim O’Reilly to say that I would be willing to give up some of my editor’s income to help other parts of the company. The situation must have been dire, because I got a phone call from Tim where he said with a nervous chuckle, “Andy, I think I’ll take you up on your offer.” All the editors had to make a sacrifice to keep the company afloat. It may be a sign of privilege to make a personal sacrifice for the greater good, but recent world history suggests that privilege has not bestowed that quality on most of the wealthy “one percent”. For some reason, it seemed instilled in my bones.

Stereotypes make it easy for people to pigeon-hole issues on which they don’t want to expend thought. One way the average person has tried to deal with the importance and financial success of computer programmers in our lifetimes is to adopt the slur that programmers, perhaps congenitally, lack the skills for social interaction. I have discovered a full range of personality types among programmers and other computer professionals. Some, it is true, show impatience with the small talk about pets and traffic that populates many everyday conversations. They prefer to seek out people who can speak at their intellectual level about things they like to do. But the craving for community is strong, and spurs them to cross oceans for conferences many thousands of miles away. There, they can go from dawn until late in the wee hours connecting with people of like minds.

Certainly, I’ve encountered some curious types among the computer set. The Perl community seemed noted for odd personalities who often developed rivalries verging on feuds. On many mailing lists across the computer field, a perennial topic was how to deal with “toxic members” or just with routine insensitivity.

One leading programmer, a young man with serious thin lips, happened to sit next to me in one of the rooms set aside at computer conferences for attendees to take time out and conduct personal work. This room contained a couple dozen hackers wrapped up with their laptops, so the atmosphere was rather unsocial to start with. This may have colored the programmer’s mood as he noticed that his laptop was low on battery power, glanced over to see that my laptop took up the nearby wall socket, and then poked his nose at my screen to determine that my laptop had twice as much power as his.

A normal person might have said, “Excuse me. I notice that your battery has a lot more charge than mine, and I need to do some important work before my laptop loses its power. May I use the socket you’re using?”

But this is what he did instead: Abruptly pulling my plug from the socket, he said as if citing a rule from some community guidebook, “I have only 16% battery power and you have 34%, so my computer takes precedence.”

Rudeness can also be an emotional adaptation to chronic disappointment. Those of us who bumbled our way into the computer field while young have weathered several generations of that fast-changing industry, a pace that can bewilder and all too often sideline its leading members.

Thus, at one Open Source Convention, I ran into a founder of the early social media company Friendster. She expressed a good deal of resentment, which I attribute to her entering the field too early and being forced to stand by as a witness while MySpace and then Facebook reaped unconscionable amounts of money using the concepts and even the terminology her company pioneered. She channeled her anger into the lack of recognition women suffer from in computing, which was and remains an important critique. I tried to mollify her by mentioning that I had written up an interview I had with Margo Seltzer, an important manager who emerged from the BSD community and eventually became an Associate Dean at Harvard University. The Friendster founder snapped back, “Who gives a fuck about Harvard? I started a company!”

The occasional irksome encounter at a conference—which under-represented groups no doubt suffer from more than I do—provides mostly spice for the many unexpected meetings that reveal an unexpected common humanity. For instance, I sought a meeting at one health IT conference with the founder of a small company. He told me that he was excited to meet me because he had checked my Twitter feed after I made the inquiry, and found a tweet that won him over.

What was this tweet? Some insight into technology, some apt observation on the health care field? No. What happened is that, as part of my research into big data, I had found an Israeli app that tracks Arab terror attacks and presents them on a map. I wrote that I would approve of such an app if it included Jewish terror attacks. The company founder, a Palestinian, saw in me a sympathetic observer he could talk to.

So there was no finer opportunity than a good conference to meet new people. Even later, in an age of high-speed telecommunications, conferences offered the highest bandwidth by far for information exchange. Everyone who was anyone had to attend. Right up to the COVID-19 clamp-down on meetings in person, conferences provided a critical social and community-building function.

Everyone understands that what happens outside the session halls is the most important experience, although many fine conference sessions have inspired people as well. I have explained repeatedly in this memoir that conferences were the focal point of O’Reilly’s community-building and its research. I hope that the personal stories I recount in this chapter will help you see the importance of conferences, if you haven’t experienced it yourself.

The greatest conferences bring together the leaders of movements. Debates are saved up for discussion at the annual conference, where decisions are made that drive the field for years to come.

Can a conference achieve even more? Yes, it can make a statement that fans out across the community and the general public, opening eyes to a trend that had been previously overlooked. Perhaps it can augur the future.

O’Reilly’s Perl conference did all these things. One of our marketing managers decided to take on the steep challenge of putting on a conference, with no prior experience, because the company could see Perl coming to occupy a unique and central role in computing that fell outside the horizon of the trade press. O’Reilly sensed that we had a story to tell that would benefit our product line while giving insight to managers and users throughout the computer field. At the same time, the Perl Conference gave Perl programmers and hackers of all persuasions a place to gather, as well as a platform for Perl creator Larry Wall. Small conferences about Perl had been cobbled together by volunteer enthusiasts before, but they were easy to ignore outside the community. An O’Reilly Perl conference was news.

We also took risks in program choices. Many conferences bring in a keynoter who does not address the theme of the conference directly, but proffers an expert viewpoint from another field that attendees will find relevant. (I’ve delivered a couple such keynotes myself, about peer-to-peer and about government adoption of open source.) Going further, O’Reilly’s conference tradition included—along with the usual corporate pitches that sponsors insist on—keynotes that expanded the minds of participants more than conventional keynotes. The prototype for this approach, I think, was a keynote Andrew Schulman delivered at the first Perl conference.

Schulman was a Windows programmer with no knowledge of Perl at that time. He had recently joined O’Reilly to help us expand our reach and add some sparkle to our editorial message. His keynote at our conference had nothing to do with Windows or Perl. Instead, he helped the audience think about the evolution of the Web, which was moving from static content to dynamic pages generated upon demand. I particularly remember his showing how FedEx (a legacy company that seems to be doing fine, even though more and more documents are taking digital paths to their recipients) used the Web as a doorway to its database and the links (URLs) as a programming tool.

Every single FedEx package had its own web page, with what Schulman called “the URL from hell”. But the page didn’t exist until the customer clicked on the link. What happened next was described by Schulman in his review of this memoir: The incredibly long URL “invokes a process on Fedex’s server to dig into Fedex’s database in real time and turn the information there into a web page on the fly. My larger point was that URLs are a way of doing remote computing, i.e., invoking processes on other systems. The programmer and author Jon Udell was making this same point at around this time in articles in Byte magazine.” A pretty nifty idea to air in 1997, when few were talking about URLs as universal identifiers and about the Web as a vast database recording the world’s transactions.

In retrospect, our sponsorship of a Perl conference heralded the beginning of a shift in computing so transformational that the term “tectonic” would be understating the case.

Perl was becoming popular because system administrators were becoming programmers. This was the glimmer of the DevOps movement that matured and found itself a firm place in corporate development a good 20 years later. Programmers and their companies started using the term DevOps in the 2010 decade as they noticed the traditional walls breaking down between the development teams and the operations teams who were responsible for getting the programs into everyday production. Operations were getting automated, looking more and more like the programming that developers did.

The most imperative driver of modern system administration was the speed-up of social and business change, which since the 1990s whipped companies to create and upgrade applications at an unprecedented pace. Software came to undergird more and more businesses, and these businesses became dizzy over its potential speed of change, as at Facebook with its notorious slogan, “Move fast and break things.” Managers pressed for changes by the hour or minute for all kinds of goals: to respond to threats, to fix bugs, to try new features on selected groups of guinea pig visitors (A/B testing and bandit testing), and to roll out permanent changes. The impatience of the mobile consumer was matched by the impatience of the corporate planner.

Programmers could not achieve that pace through the traditional process: development first, then testing by another team, and finally deployment by yet another. Each stage introduced friction, required its own set of tools, and made one team dependent on another possibly unreliable team to meet its deadlines.

The logjam was broken by new tools for automating the steps in testing and operations. A new approach to connecting programs called RESTful APIs, which ran over the Web like the peer-to-peer services I have described elsewhere, provided a lightweight interface that programmers could easily learn and that every programming language could support. This in turn led to the unification of all development and deployment. It seems inevitable that these trends would make Software as a Service more and more attractive, because no one wanted to distribute new software to users at that pace. We have come back to the factors driving cloud computing that forced their way into the beginning of this memoir.

The merger of programming with system administration represented by DevOps wasn’t happening at all in 1997 when O’Reilly launched the Perl conference. But the groundwork was being laid. System administrators were dealing with larger and larger installations of more and more complex systems connected in multi-layered networks—and failing more often in ways that were more difficult to fix. System administrators thus needed automation, and they learned to program so they could have eyes everywhere to monitor everything and could relieve themselves of mundane fixes and other tasks. I see that as a key step toward DevOps.

We didn’t say all that at the Perl Conference. But we helped prepare the table for the feast. Also like other fine conferences, this one covered a wide range of ideas beyond the Perl language itself, as demonstrated by the keynote I mentioned by Andrew Schulman. According to one record, Eric Raymond also gave a speech at the conference based on his ground-breaking article about free software and community-based innovation, The Cathedral & the Bazaar.

Logistically, the conference was also a tremendous success, a tribute to the marketing team who took it on without experience in the field. We put on a second Perl conference next year and then expanded the scope of the conference even further, calling it an Open Source Convention and covering whatever was on the minds of programmers using free and open source software. I remember one year that the different programming languages we covered were awkwardly segregated—which does not engender healthy conference interactions—each being assigned a different hallway in locations scattered through the hotel hosting the conference. I felt a chilly sadness walking through each hall, as if entering the vault of a forgotten archive. When we grew large enough to occupy a more standard convention center, whether in Portland or in San Jose, California, all tracks were physically integrated.

I’ve had the good luck to receive a couple conference invitations through authors who fell behind in their writing and felt guilty. They apologized for their missed deadlines by giving me the opportunity to travel and participate in some curious events. These authors didn’t realize that many other authors behaved far more irresponsibly, and perhaps didn’t see past my personal relationship with them to understand how their failure to produce their books affected O’Reilly’s revenue and product line-up.

Anyway, in the mid-1900s I received an unusual invitation through an author who worked at Microsoft. A major new web service called Windows Live was in gestation, so the company was convening a couple dozen people they considered leaders on the Web to review early plans. I don’t think I had anywhere near the knowledge and depth of experience displayed by the other exalted attendees, but my author wangled me a place on the team.

It was a very congenial group of people to caucus and dine with. Microsoft paid for everything: our trips to Seattle, hotels, meals, and a gift certificate worth over $100 that we could spend in their campus store on our last day before flying home.

We were all hackers at heart. We would have been happy staying at a motel and having a burger for dinner, but Microsoft put us up at the prestigious W hotel and brought us to toney restaurants for hors d’oeuvre and fine meals.

The W was quite an experience. I don’t remember what the room was like, probably because I’m normally oblivious to my surroundings, but I did notice that each floor had, opposite the elevators, beautiful eighteenth-century architectural sketches. They were originals, I think. I have always loved galleries, and the elevator landings of the W Hotel formed a 24-story gallery. I took the elevator up and down one day, floor by floor, to check out different sketches in four or five hallways.

I was also in the W lobby one day for a strange sonic experience. They piped in techno music, which I suppose was supposed to flaunt hipness while establishing a relaxed ambiance. At one moment, I heard the techno fade out and the famous Adagietto of Mahler’s fifth symphony come on. After ten minutes, the Adagietto finished and the techno resumed.

But let’s get to the point of the meeting. What was Windows Live? To understand it, you have to put yourself back into the 1990s, to think of who dominated the Web at that time, and to grasp the size of the transition Microsoft was going through.

The Web was started by scrappy independent writers, resolutely democratic and decentralized, but as the Internet revolution brought millions of people online and the Web became popular, large companies angled to take it over. CompuServe and America Online, which had prospered through private networks, sought to create similar circumscribed settings on the Internet. Like Apple, which created its iPhone store to let outsiders participate under strict controls, these big companies were afraid of the open Internet, sensed that part of the public was also afraid, and wanted to provide a feeling of community and connectedness while keeping the companies as benevolent if slightly fusty chaperones. Critics called these offerings “walled gardens”. By the time Microsoft realized that the Web was a big deal and that they had to be there, Yahoo! had become wildly successful by offering weather reports, movie reviews, and other detritus on a site called a “web portal”.

So basically, Windows Live was meant to be Microsoft’s web portal. To our motley team of reviewers, Microsoft presented a set of mocked-up screens and talked about how the visitor would navigate through them, a process we now call User Experience or UX. The screens and UX were pretty unimpressive, and we all gave candid critiques.

After the sessions and meals and hallways conversations, we had our shining moment in the Microsoft store. Some of the team members were like kids in a toy shop, snapping up things like whatever game console Microsoft was pushing at the moment. Still the big free software advocate, I looked around and saw hardly anything of interest, so I saved my coupon and handed it over to the editor back home at O’Reilly who was in charge of our Microsoft book program. What I still preserve from this adventure is a black nylon/cotton jacket saying “Windows Live” on the back, appropriate to pull out on the first crisp Autumn days each year.

I believe Microsoft eventually did launch Windows Live, and it went across about as well as the Microsoft store did with me. I don’t think Microsoft really developed much of a Web strategy until it mimicked Amazon.com’s successful Amazon Web Services with a Microsoft cloud offering called Azure. By this time in the 2000s, the various large companies were implementing the walled garden concept once again, this time as cloud services for programmers and data scientists. And that harks back to the very beginning of this memoir. But I have one more set of memories to share before wrapping up.